5. Reinforcement & Punishment

The front image of this chapter shows the conceptual framework that has been developed for pulling together the basic findings of research on how behaviour changes as a consequence of interactions with the environment. These findings are derived from studies that have examined how the frequency or future likelihood (i.e., the probability) of a behaviour is affected by consequences. It turns out that there are two basic effects on the probability of behaviour. Apart from remaining unchanged, the probability can either increase (i.e., Reinforcement effect) or it can decrease (i.e., Punishment effect). It really is as simple as that, at least at first glance.

There are, however, quite a number of other considerations to be noted, some of which are technical in nature and some of which concern the ways in which basic findings can be used in applied settings (e.g., Education). In this chapter we will look briefly at some of these issues and we will provide links to where they are discussed in more detail.

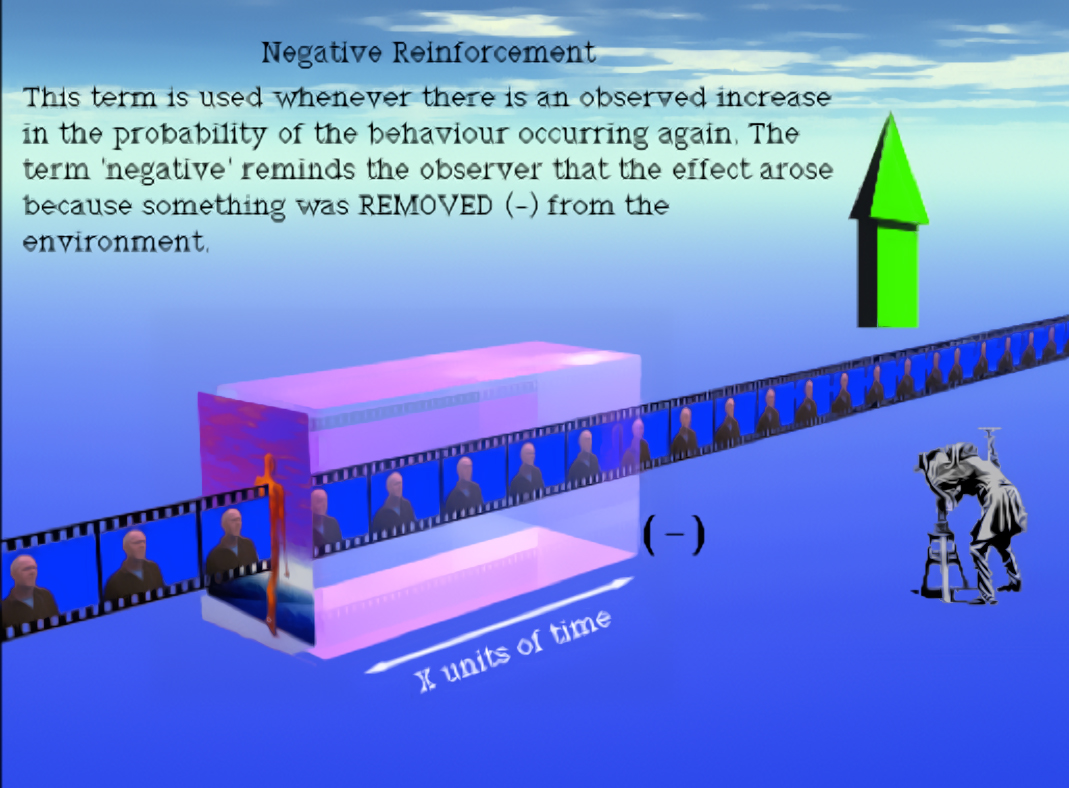

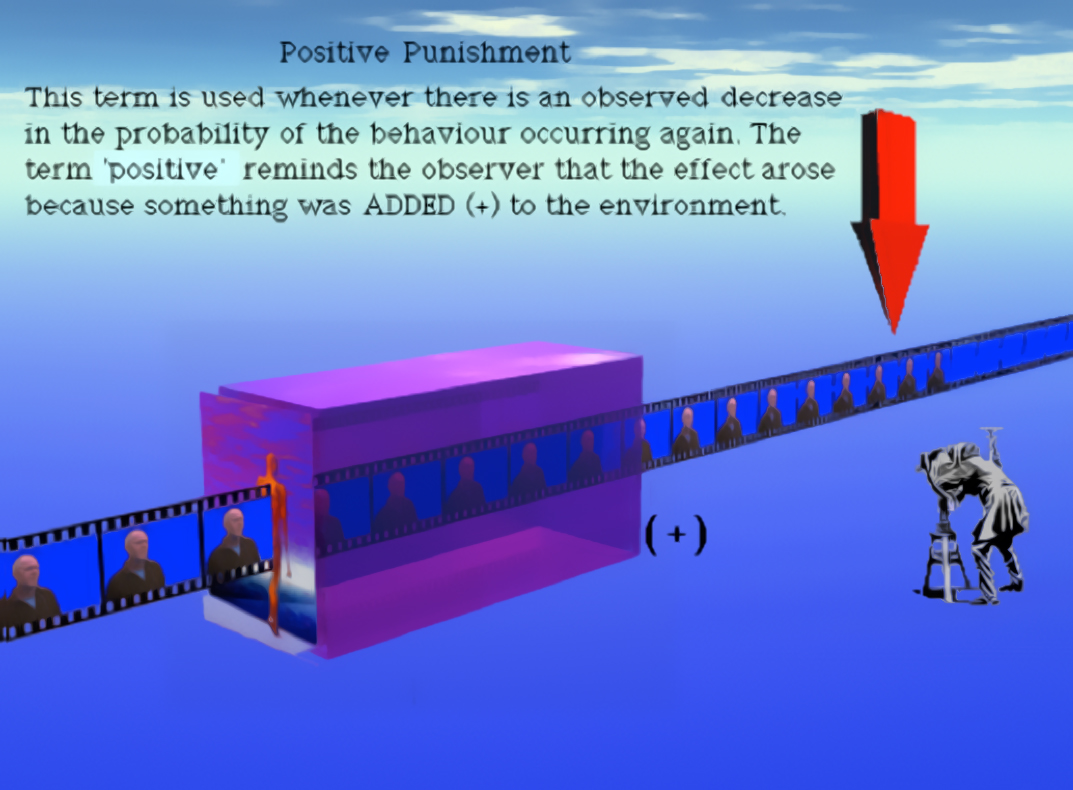

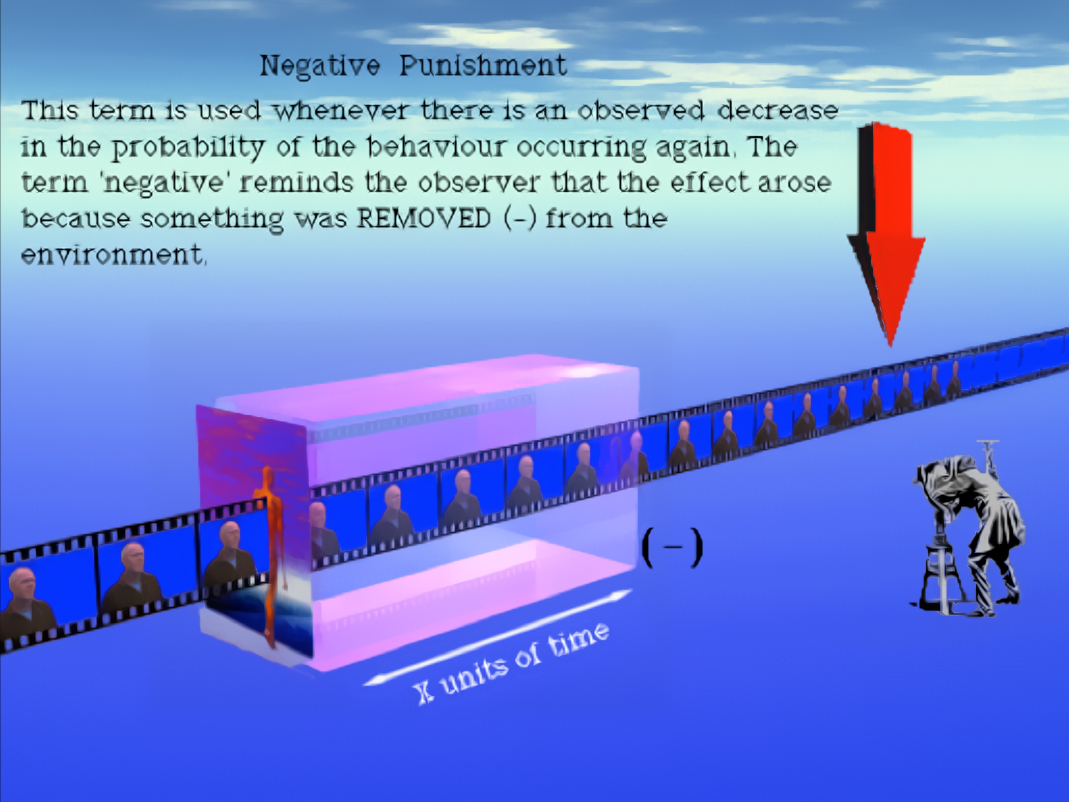

Our starting point is to note that, under the headings of Reinforcement and Punishment in the opening image, there are two other terms, ‘positive’ and ‘negative’. These terms refer to aspects of any procedure that results in either a reinforcement or punishment effect. The term ‘positive’ in this context refers to the fact that something was added to the environment as a consequence of the behaviour. The term ‘negative’ refers to the removal of something from the environment as a consequence of the behaviour. Students often get confused at this point so let’s see if we can prevent any confusion by getting you to remember two points before you analyse the procedure responsible for a behaviour. When you see behaviour occurring with a high probability, or at a high rate, then, whatever the procedure, you may be witnessing an example of a reinforcement effect; ideally, though, you would need to see the behaviour prior to this observation to judge whether there has been an increase in the probability of behaviour. The opposite is true if you observe a very low rate of responding; again, though the low rate would have to be relative to a previously higher rate before we can call it an example of a punishment effect. So, think first about how the probability of behaviour has been affected to help you understand whether you are observing a reinforcement or punishment effect. The next step is to see if something was added (positive) or taken away (negative) as a consequence of the behaviour.

Contingency

If it is observed that certain environmental events occur only after a behavioural event has occurred, then the term 'contingency' is used to refer to the relation between these events. Putting it formally, a contingency specifies an IF-THEN relation between two events. The existence of a contingency between behaviour and an environmental event crucially determines the future probability of behaving. That is to say, an environmental event itself does not function inevitably as a reinforcer.

This can be seen easily from an experiment involving an animal that has been trained to press a lever for a food reinforcer. In this instance, the experimenter has arranged a contingency between lever pressing and food delivery so that the absence of lever pressing results in the absence of food delivery.

A simple way to examine this contingency is to break it and see what happens. We can break it in either of two ways:

(a) Lever pressing no longer produces food. If this were to happen, the animal would stop lever pressing. Nothing too surprising there!

(b) Food is delivered non-contingently, i.e., it is delivered freely so that lever pressing is unnecessary to produce it. If this were to happen, the animal would stop lever pressing.

A human example of such non-contingent delivery of environmental events can be seen in many residential homes for older people. It is quite common to find older people who are physically able but who are ‘robbed’ of their independence when everything is done for them in the care home; their self-esteem disappears and they get depressed. Studies have shown that when they are given back control, even over some basic contingencies such as preparing their own food, they can become revitalised and feel much better.

Operant

In any science, scientists have had to invent many new terms to help them deal with the complexities that arise in the study of a particular issue. In Behaviour Analysis, the term 'operant' is one such term. It was coined to help deal with a common observation that more than one behaviour will produce the same environmental event. For example, there are many ways to write a sentence, ask a question, begin a relationship, greet someone, or study for an examination.

B. F. Skinner dealt with this complexity by noting that on many occasions discrete behaviours constitute a 'class' of behaviours with a common function. That is, as a class of behaviours they ‘operate’ on the environment to produce the same effect. The word 'operant' is derived from the word 'operate' and it is used as a label to refer to a class of behaviours with a common function. In fact, when behaviour analysts talk about how certain consequences affect the future probability of behaviour, they implicitly refer to operant behaviour.

Reinforcement + (Positive)

Reinforcement - (Negative)

Punishment + (Positive)

Punishment - (Negative)

Motivating operation

The reinforcing effectiveness of any consequence varies from time to time. In lay vocabulary we refer to this fact when we say that someone is/isn't motivated.

“For example, water is likely to be an effective reinforcer if someone has been deprived of water for some time, but it is less likely to be so after a large quantity of water has been consumed. The things that can be done to change the effectiveness [i.e., environmental manipulations] are called establishing operations. Deprivation and satiation are two examples, but they are not the only possibilities.’ (Catania, 1994, p. 26)

During the shaping exercise shown earlier with the student, we saw how instructions ensured that a simple buzzer functioned as a reinforcer for his behaviour. We could say that this instruction functioned as an establishing operation for the buzzer. A motivating operation is defined as an event that momentarily alters (1) the reinforcement properties of a reinforcer and (2) the frequency of occurrence of the behaviour relevant to those consequences. In principle there are two kinds of motivating operations; an establishing operation increases the reinforcing properties of a reinforcer, while an abolishing operation decreases the reinforcing properties of an environmental event. In other words, something can happen that makes a reinforcer stronger (establishing), for example on a hot day, a cool drink may be a stronger reinforcer than usually. On the other hand, something can happen that makes a reinforcer weaker (abolishing), for example on a wintery cold day a cool drink will not have the same reinforcing effect as in the summer time.

Motivation operations can be unconditioned (such as deprivation or satiation) or conditioned, with value-altering effects that are a result of the organism’s learning history.